Focusing on what truly deserves our attention, rather than mindlessly succumbing to the allure of glowing screens, is a challenge worth pursuing. But if we want to learn more, grow more, and understand more, we won’t stop there—we’ll also take time to reflect…

-

-

I have coffee with a friend whose youngest child just started full-time school. Afterwards, she sets off for the pool—alone! Only herself to strap into the car, to change. No tantrums, no complaints—bliss! At three, the school bell rings. As we embrace our little loves she tells me how, post-swim, standing in the shower, she felt an intense loneliness. All those years we long to be alone, just for one minute, one hour. All those years our children cling to us and then, we leave them—six hours, five days a week. We leave them and, are left.

-

For generations, parents have approved, and disapproved, of the people their children have chosen as friends and romantic partners. The next generation of parents will face a new challenge: there’s no guarantee that all their children’s friends, or future lovers, will be human.

-

Few would challenge the notion that, in order to properly think a question through, we need at least some time alone with our thoughts. Some might even claim we can’t think for ourselves unless we are thinking by ourselves. But a new book by a public philosopher, based on the wisdom of an ancient philosopher, reminds us that inviting others to “intrude” into our “private mental world” and think with us, makes sense.

-

I found myself down a rabbit hole this week. I was wondering what those who are most excited about generative AI — those using it to write everything from personal emails to public presentations — wouldn’t use it for? How many, if asked to write a speech for their child’s wedding, or a parent’s eulogy, would draw the line? And how many would not think twice?

-

What is generosity? Intuitively, we know when an act is generous, and when it’s not. But try to nail down the boundaries of generosity, and things get slippery. Just ask Peter Blake, an associate professor of psychology at Boston University, who has been studying generosity in children for more than a decade. Even he struggles to define it.

-

The notion that time spent in the home is somehow wasted, is a relatively recent one—but it’s quickly become widely held. Helen Hayward’s 2023 book Home Work: Essays on Love & Housekeeping questions it. In times when couples and families can and are seeking to divide labour more equally, when society is trying to give working women the same opportunities and pay as men, and when technology is promising everything but an escape from housework, Hayward elevates it as worthy of time, effort, and attention.

-

A few weekends ago, I made a parenting mistake. I didn’t realise in the moment. The penny didn’t drop, until a good friend made a comment afterwards.

My family was hosting a brunch with several other families. After a few hours in the noisy, sticky, fray, one of our kids asked to retreat. Sensing my hesitation, he pointed out that none of the other guests were of his age.

-

My mother kept them – her two favourite childhood dresses – first, in case she had a daughter; then, in case I did. Both were pale-blue cotton, with tiny graph-paper-sized checks, cup-like sleeves and flowing knee-length skirts. One, with a Peter Pan collar and a proud display of smocking on the front, was made by my grandmother, but the one my mum liked best was shop-bought, with bright flowers embroidered round the hem. She remembers wearing it when she was old enough to put on socks and shoes but, to her frustration, not yet allowed to go to school.

-

Christina Baehr runs an off-grid hostel in the Huon Valley while raising (and homeschooling) her huge family. She’s not famous, and she’s not rich, but in her first year of publishing she doubled her household income.

-

When Megan Tudehope decided, aged 40, to write her first novel, she started reading and watching anything and everything that might teach her how, and she noticed a common theme: people talking about how they’d wanted to be authors their whole lives, and had been writing since childhood; who had written their first novels in their 20s, if not their teens. Tudehope, who grew up convinced she couldn’t draw or paint and therefore wasn’t a creative person, never thought to write a novel in her 20s—but she did have an idea for one.

-

Last year, I was at a birthday party, sitting with a group of “can’t-dance” friends, discussing our incompetence. Instead of just moving with the music, we would think about what our bodies were doing, or not doing, making carefree dance impossible. We had learned how not to dance. If we wanted to dance — naturally, unselfconsciously, without set steps — we had some unlearning to do.

-

There’s an analogy that people use sometimes, in cases where it’s hard to draw a line. It involves thinking about grains of sand, and the precise point at which a growing gathering becomes a heap.

Writing about the relationship between the problem of climate change and the impact of individual actions to reduce emissions, Catriona McKinnon discusses the “sorites paradox”—the idea that because removing one grain won’t destroy a heap, removing the next grain won’t either, nor will removing the next or the next.

-

If I were a reviewer at a writers’ festival and I spotted an author whose work I’d praised – but also criticised – I’d be tempted to look the other way.

But, far from avoiding Christos Tsiolkas at last year’s Canberra Writers’ Festival, literary critic and Festival Artistic Director, Beejay Silcox chose to share the stage with him.

-

I don’t keep a gratitude journal. If I did, there’d be multiple entries for the times I’ve been greeted by a friendly passer-by when on a morning walk. I’m even more appreciative than I used to be, because the number of people who return—let alone initiate—a greeting, seems to be shrinking.

The other day I caught myself thinking less about the dog-walker who cheerily returned my “Hello!”, than the several other exercisers who either looked through me or gave a puzzled stare. Did they see me? Just not hear me? What were they thinking? Do I know this woman? I hope she isn’t talking to me!

-

I can see why kids who find themselves at a holiday shack where the only screen-based entertainment is an old TV would be perplexed. By the time you explain all the things the remote “control” doesn’t do, all you’re left with is a limited number of viewing options at any given time, and no control over when each starts or stops.In the age of smartphones and streaming, you could call it “dumb TV”. Or you could sell it as unique, novel, a game: “surprise TV”.

-

Given what money-spinners weddings can be, I guess it’s not surprising that divorce is now big business too. I didn’t see divorce gift registries coming, but I can see how they make sense.

In I Didn’t Want Wedding Presents. But Gifts Helped Me Survive My Divorce, Leslie Jamison writes about how she didn’t need a gift registry when she married: combining two households necessitated getting rid of stuff, not acquiring it. But people still gave gifts, and she still treasured them.

-

The shops were just starting to proclaim the coming of another Christmas when I came across an antidote to overspending and overconsumption. I wasn’t looking for it, in fact. I was listening — to an interview with novelist Claire Keegan. In it, she talked about how she never wants to give her readers “too much”.

-

Two of the dearest neighbours my family has ever had were elderly widowers. Byron shared a fence with us, Mario lived opposite. Both were eager gardeners, both loved our kids, both showered us with gifts. Byron, a retired police officer, often popped up from behind his fence to chat. He’d comment on the weather and the news, on the lotto jackpot that he never won but often invested in, pledging us a very generous share. He would pass us vegetables, slowly grown, quickly given. There were ice-creams too, whole boxes of choc-wedges, for the kids. He’d joke they’d fallen in his trolley at the shops, acting all surprised, and the kids would play along with happy grins.

-

Last year my marriage turned 18. The glue for my (our) marriage has been love, friendship, commitment, shared values and beliefs… no surprises there. What has surprised me is how important humour has been. Looking back, the fact we’ve taken marriage seriously, without taking ourselves too seriously, has, in all seriousness, helped us to stay (happily!) married. -

As far as I’m aware, I’m not dying – yet – but that didn’t stop me from contacting a comedian about my funeral plans recently.

It started when my husband sat me down and told me I had to watch something. That something was one of New Zealand comedian Josh Thomson’s stand-up routines.

-

The photos arrived via SMS. They featured my 87-year-old great aunt standing beside a world-famous fashion designer, beaming. In one of them, the designer is smiling at my aunt instead of the camera. In another, my aunt’s head rests on the designer’s shoulder. Each has an arm around the other. They look comfortable, relaxed.

-

In the famous phrase “murder your darlings”, “you” are a writer and your “darlings” are the parts of a piece that, despite your love for them, must be scrapped. The work itself is the ultimate darling, which makes such scrapping possible. Once finished, the challenge is to find that work a home.

Before I started freelancing, I assumed my greatest challenge would either be the task of writing (and of murder), or of finding my writing a (paying) home. What I’ve since discovered is that, as hard as writing, rewriting, and finding a home is, what happens next is very often harder still.

-

When he was a child, Bob Burgess once mentioned to his mother that he didn’t really like Christmas. He still remembers how she looked at him with “abrupt anger”, and then began to cry. At the time he was puzzled. Now he can see how hard Christmas would have been for her. His father was dead, and his mother had very little money. The fact he spoke those words to her still fills him with regret. At the age of 65, the holiday season saddens him, and he understands this memory is the reason why.

-

It’s true. I swear. I remember when you were allowed to drive a car—even a four-wheel drive that emitted more than 200 grams of CO2 per kilometre, even if you were the only one in it, even if you could have caught a bus—all day, and only pay for petrol. No fines, no charges.

As for planes, if you had the cash you could fly as often as you liked—no records were kept—and often there were empty seats. There was even this thing we called ‘first class’, where you could pay for twice as much space as all the other passengers.

-

It wasn’t an art exhibition, though it did feature elements of sculpture and performance art. On paper, it was just another activity at just another school fair. The activity was (to try) riding various bicycle-like creations that had been cobbled together from parts — or to watch from a safe distance.

-

A stranger at a shopping centre once caught my attention. She’d been speaking with a man, but interrupted him to talk to me. Quietly, kindly, she told me that my fly was not done up. Surprised and embarrassed, I laughed, thanked her, and pulled it up.

Months later, the moment came to mind when I was listening to a conversation about “the bystander effect”: our reluctance, when others are around, and we see someone needs help, to intervene.

-

Dr. Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela is a woman with a vast imagination. She’s capable of imagining changes of heart that many would dismiss as impossible. She can imagine people who have committed terrible atrocities, and the people they have hurt, turning toward each other instead of turning away. But she’s realistic, too.

-

Two books that I picked up recently — Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead and Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song — have a great deal in common. Both are timely tales of injustice, darkness, and despair. Both explore evils that many in this world, through no fault of their own, cannot escape. Both use a relatable main character to make sure readers care. And both, once I had finished reading them, were not finished with me.

-

At first I said “no” when my eldest child asked me, at a family gathering, if he could play a joke on the unsuspecting crowd.

He wanted to make and offer round some cordial — spiked with salt. Mine had attracted complaints because it was too weak. This would attract a taker because it would be strong.

-

Every person who reads this, whether passionately religious or passionately anti-religious, will have beliefs about how our world came to be—about what is, and isn’t, possible. To some extent, those beliefs will have been shaped by words.

-

There are limits to what a human being — and human beings collectively — can understand. We know this and, day after day, we forget and are reminded. I’m not just talking about what we can understand about history, or physics, or chemistry, or ecology. I’m talking about what one human being can understand about another, even their self.

-

One of the most diligent high performers I know has a theory about workers and their competence. He mentioned it in passing recently; I’ve since heard many stories that it could possibly explain.

The idea? Eighty percent of people aren’t good at their jobs.

-

T: On the island—

H: —they’re mad.

T: Shooting a hare is no big deal.

H: It’s nothing; it’s a great sport.

Me: Are they hard to shoot?

T: Well they’re very hard, because they’re so clever they can—

H: —zig-zag—

-

What captivates me most about eucalyptus leaves is the ways in which their skin transforms with age—with exposure to the elements, disease and nibbling prey—with suffering. Colours bloom like bruises as leaves lie upon the ground; damaged, fragile, dying and yet beautiful, dignified, unique. Each skin tells the story of a life.

-

I still remember my astonishment when an Australian PM, at a campaign trail event—the kind where hands are shaken, babies kissed—picked up a raw onion and took a bite from it.

If I saw the clip of that farm visit now, I might declare it a deep fake. Could someone really be so determined to please, so delighted by fresh produce, or so sleep-deprived—that they’d not only bite an onion but, still smiling, swallow too? Surely it was just an apple, digitally manipulated for a laugh.

-

I was clicking a link that should have taken me to a review of a children’s book, when my computer screen flooded with porn. I couldn’t close the window fast enough or – judging by the speed with which other family members flocked to find out what on earth was wrong – shriek loudly enough. It was like the time I was stung by a bee and a neighbour not only heard, but was so concerned she knocked on the door to check no one needed an ambulance. -

There are more organisms, living in a teaspoon of rich, healthy soil, than humans in this world, research has found. I can’t tell you how “healthy” has been defined, or how rigorous the research was, but either way, I find it wonderful. Humble, not so humble, dirt.

And then there’s dust. Since learning that it’s made from cells of human skin—and, according to one study, also paint, pollen, fibres, minerals, mould; hair and viruses and ash and soot; insect body parts, bacteria, material, bits of soil—I see it differently. It contains traces of families, history, life. It’s almost sacred when you think of it this way. And isn’t it, poetically, from dust and dirt we came?

-

Before explaining how to read rhythm on a page, my children’s piano teacher gave the class a challenge. She asked the kids to walk around the room without consistent steps — no repetition and no pattern. If you’ve never tried this, try it now. You might find you have to hop and skip and jump to keep your feet from falling — unintentionally, automatically, irresistibly — into a steady beat.

It’s a simple challenge. And it’s absurdly difficult. It shows that when we’re walking normally, we do so rhythmically, and unthinkingly. Even if we walk unevenly, our steps still fall predictably: ba-dum, ba-dum, ba-dum. It’s natural, effortless.

-

An advertising campaign that claims AI is no match for authenticity, and seeks to show the world that “instant isn’t always better”, has sprung from an unlikely source.

Earlier this month, a competition on a government-run tourism website in Tasmania invited members ofthe public to submit creative prompts for artworks “set” in the state. Now, those selected by participating artists are being turned into physical, human-made art. When each piece is complete, the person who penned the prompt will receive the resulting art.

-

I let him run ahead. He knows to stop before the road; he always does. But there’s always a chance that this time, unpredictably, inexplicably, horrifically, he won’t. I watch him running towards danger and I do not intervene. I think: This is what it is to be a mother. I cannot always hold his hand. Sometimes I’ll have to let him run, to pray he won’t forget what he has learned. I think: I’m close enough to see, but not to save. I think: I am a parent now. I will do this for the rest of my life.

-

Even if you’re sure you’d hate camping, I recommend you try it at least once. Because after camping you’ll notice aspects of every other holiday will have elements of luxury, from packing and unpacking to showering and sleeping.

I can’t remember my first camping trip. I grew up with a mother committed to ensuring her children saw as much of their home state as possible, even if this involved excessively long drives to the middle of nowhere. I was also a Brownie then a girl guide. I liked camping, I had friends who liked it, later I married a guy who liked it, and we had kids who did too.

-

There’s a moment in Elif Batuman’s latest novel when its protagonist wonders whether, instead of trying to write a novel that’s true to life, she could manipulate her life in order to produce one:

“What if I could use the aesthetic life as an algorithm to solve my two biggest problems: how to live, and how to write novels? In any real-life situation, I would pretend I was in a novel, and then do whatever I would want the person in the novel to do. Afterward, I would write it all down, and I would have written a novel, without having had to invent a bunch of fake characters and pretend to care about them.”

-

The problem of what to buy a loved one who seems to have everything they’d ever want is one many of us face each year, as is a desire to avoid spending beyond our means, or contributing to landfill. But there’s an alternative. If a person is hard to buy for, don’t buy them anything. Make something instead. What matters is the thought.

You might hear the words “make something instead” and think of spray-painted pasta necklaces and collages that contain more glue than shells; or of people who can actually knit things that other people actually want to wear.

-

One of the first things I learned when travelling in Europe, knowing only English, was to prioritise learning the word “sorry” when preparing to enter a new country.

There’s nothing wrong with learning “hello”, “thank you” and “please”, “I am…” and “where’s the nearest…”, but if you’re going to learn one word by heart, that’s the one I’d recommend. If you get yourself in trouble, it will likely be the word you need the most.

-

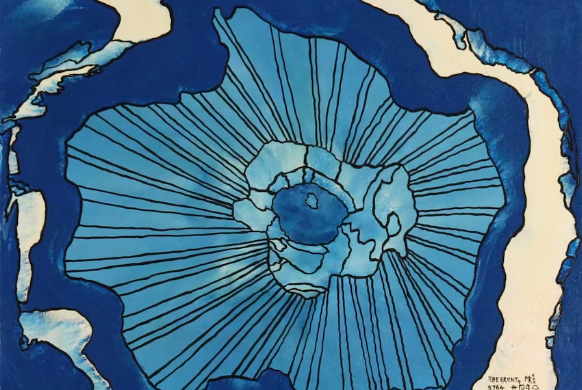

Last month I came across the story of an extremely “quiet” achiever: an Australian maths teacher who lived alone and, after retiring, started painting abstract art alone. Over a twenty-year period, he produced more than 7,000 paintings — naming, dating, and numbering each one.

After his death, his sister called them “rubbish” and told an estate auctioneer to get rid of them. But they didn’t look like rubbish to the auctioneer and, when he showed them to an experienced art valuer, she agreed.

-

I was packing for a weekend away with several other families when I made the mistake of thinking a bottle of red wine would be safest rolled up in a sleeping bag.

I didn’t know most of the families going but I knew the instigators, and that they’d have gathered a great crowd. Those other families probably thought so too – until ours showed up, reeking of wine, in the middle of the day.

-

On Australia’s island state, winter feels much longer than a season. It arrives before we’re ready, lingers long after we tire of its exhausting company. In the dark middle weeks, the daylight hours shrink, the nights are long; wind and shadows have the touch of ice. Our neighbour, named Antarctica, feels closer than she is.

Even in the thick of it I know that spring and summer still exist – will come again – but believingthis takes faith. The memory of that other time begins to fade, to feel like fantasy.

(more…) -

The main thing I learned in science class, apart from the fact teenagers can’t be trusted with Bunsen burners, is that experiments should begin with a hypothesis and end with a conclusion. You can’t jump straight to the conclusion. And yet, outside of science labs, when we’re making judgements in the world — especially about fellow human beings — that’s what we tend to do.

I’m not saying we can, or should, devise experiments to somehow test our assumptions about each other. I’m just wondering…

-

One of the biggest shocks I had this year wasn’t the sound of my car scraping against another car, and the realisation that, in an absent moment, I’d gone straight into someone else’s lane instead of turning left. It was what happened next.

I pulled over and started vomiting apologies on to the driver of the ute I’d just scraped. I was sorry, it was completely my fault, I had no idea what I’d been thinking, or rather, I clearly hadn’t been thinking, at least not about the task at hand…

-

Our “appetite for newness” is not unique to our times, but habits of replacing not retaining are. We’re familiar with the impact on our world, but have we considered its impact on our minds?

The practice of “darning” — mending holes and tears in garments by interweaving yarn — was once a common one. Now few possess the skill, and fewer practice it. Why repair, if you can just replace?

-

There’s a story our year 11 and 12 students are hearing, one I heard at that age too, that isn’t true. The details change, but the take-home point is the anxiety-inducing idea that what they’ll do with “the rest of their lives” is a decision they must make now or very soon and that failing to make “the right choice” will have disastrous consequences.

The myth is so pervasive that they might not question it; might fail to stop and realise there is no singular “right choice” or that the “wrong” choice or even score needn’t rule out future flourishing.

-

I came across a surprising claim the other day. Shortly after reading that in the last 200 years, Australia has suffered the largest documented decline in biodiversity of any continent, I read that my home state’s habitat has remained “relatively unchanged” since 1936.

The quote was on a US biotech company’s website. Last year the company, Colossal, which is trying to “de-extinct” the woolly mammoth, joined forces with a team of scientists at Melbourne University who are trying to bring back the thylacine.

-

When productivity consultant Daniel Sih was writing Raising Tech-Healthy Humans, he asked his kids to think about their best experiences in life. Their fondest memories — listening to him play the guitar and read to them before bed, jumping on the trampoline with a neighbour, a family game of mini-golf — didn’t involve screens; they did involve spending time with loved ones. In his book, Sih reflects on their answers and what they had in common: they were tangible, relational, and unplugged.

-

If you were walking past a car on a hot day and saw an infant strapped within, the windows closed, what would you do? Assume a parent was nearby? Maybe scan to see?

What if nobody was in sight? Would you stop to tap the window, peer inside?

And if the child seemed motionless — eyes glazed or closed, no sign of breath — what then? Would you smash a window? Call for help?

-

A few summers ago, my grandmother saw me look twice at a dress in a department store and made me try it on. It was dusty blue and sleeveless. Its high neck fastened with a button above an open back. One sash wrapped halfway round the waist; one emerged as if by magic from a slit. I tied them in a bow against my hip. From the waist to just below the knee, generous folds of fabric flowed. When I walked, they swished against my skin. I didn’t want to take it off. Last summer, I wore that dress so often that I joked it was my ‘summer uniform’…

-

I know what’s meant by “cost of living”. I know it’s about money, the economy; inflation, interest rates. But don’t you think those words, so often chanted in the news, could be taken from, or used to make, a poem?

Cost of living. I think less about the rising price of rent, of petrol, milk and bread, than of parents sick with worry, up all night, waiting for their teen to return home; a grown man, helping a father who no longer knows his name, to bed; a schoolgirl, who sees her friend “forgot” his lunch, again, and pretends to not want hers. It reminds me of the always worthwhile, often costly task—of loving.

-

I used to think professional musicians, artists and writers were the epitome of creative success. They’d bypassed nine-to-five monotony and were travelling the world, being recognised for, and making a living from, their craft.

Twenty years on, I’ve started noticing different kinds of artists, a different kind of success: friends with “normal” jobs and “normal” lives who are still driven to create. Their ages mean they’re past their so-called prime; their circumstances mean it’s hard to find the time…

-

I recently started watching a television series with my eldest son. The more that I reflect on the experience, the more convinced I am that it’s been time well spent for both of us.

If you’d told me I’d be writing this article a year ago, and that the show in question would be Alone, I might have scoffed. Reality television has never really been my thing — it riles me when manufactured drama masquerades as “real” — and my kids get enough screen time after school without opening the gateway to evenings as well.

-

One of the most memorable birthday parties I’ve hosted was also one of the easiest and cheapest. Our eldest son was turning five and wanted to invite his whole class. I wasn’t willing to host a party with more than 20 five-year-olds, but I was willing to invite them for a play in our back garden after school.

-

Unless words count, I am not the kind of person who collects. But lately, I have found myself noticing—taking, treasuring—coloured shapes I used to walk upon.

Perhaps I have the snake to thank. Before I saw it sliding, fast across the path, before I froze and watched it simply melt away, I hadn’t thought to fix my wandering gaze on ground. Nor noticed what I had been stepping on. -

As a journalist, I often have days when I just work for my employer. A story is assigned to me, I write professionally, impersonally, efficiently – and then I have days when I write for myself; I choose what I want to say and how, and who to send it to for publication.

One is productive. It consistently results in published work and payment. The other is hit and miss. Rejection and self-doubt abound…

-

My invisible friend has an office in the corner of our bedroom. On either side of his computer sit two pots filled with grass. He mows them with scissors. On the floor by his desk is a dark, glossy palm, and on our dresser is a fern, with leaves that are translucent in the sun.My husband’s office doubles as a garden — and a music studio. Between the plants there is a microphone, speakers, a mixing desk, keys. When he’s not working for money, he’s making songs for fun. On a good day, that is….

-

…and I didn’t ask for them.

I’m not a fiction writer, but lately I keep having short story ideas. One is for a story that’s set in a productive future world where workers no longer need labour over interpersonal communication – where their instructions needn’t contain pleases or thank yous or appreciative tones, because they’re almost always directed at chatbots. Many words have fallen out of use, in the workplace, and the home; now sentiments like gratitude are fading too.

-

If you had asked me, “What colour is a gumleaf, and what shape?” this time last year, I might have answered, “Green, or bluish green; and kind of like an elongated heart.” If you had asked, “What is the colour of a dying eucalyptus leaf,” I might have answered, “Brown? Or maybe grey?”

I’ve since noticed just how differently each leaf is shaped and coloured, textured, too. The toil of living decorates their skin; it grows more coloured, detailed, complex, blemished, beautiful, with time.

-

I realized something recently, about my younger self. She assumed her elders wished that they were young again—her age, or younger still.

I continued to assume this well into my thirties, all the while not envying a younger age myself. This lack of envy should have challenged my assumption—but I wasn’t really conscious I was making it at all, so it remained.

-

I sat our three (primary-aged) children down the other day and told them … Actually, that’s not true. I didn’t even try to sit them down. But I did catch their attention when they all happened to be in our kitchen/living area at various stages of getting ready for school…

-

It started with Hetty McKinnon’s Community – a cookbook that brought new meaning to the word “salad”. Recipes called for freekeh and blood orange; pomegranate and sumac; caramelised nuts and wasabi mayonnaise. I wanted to try them all, but not make them all. On social media, I wondered aloud about holding a party where every guest had to make and bring one salad. Some friends responded with enthusiasm, others with ridicule.

-

I was out walking when my husband texted me with exciting news that clearly couldn’t wait till I got home: a prediction that mangoes, which sadly do not grow in our home state, would be cheap this summer—or at least, cheaper.

I let out an (internal) “Eeeep!”, then pressed the message. My thumb was moving to select a heart when I stopped to consider my response. I stopped because lately, I’ve been hearing a lot about how machines are becoming more like us—but also wondering: are we becoming more like them?

-

I heard some good news recently. My 91-year-old grandfather called me to test his new hearing aid. For the first time in a long time, he could hear my voice. It thrilled us both.

He and my grandmother had been trying to replace his previous hearing aid for more than a month but confusing instructions, impatient explanations and faulty hardware… -

We’d spent the weekend in Westerway, Tasmania, a town whose population could fit on a large bus. He was waiting on the main street, one bulging pack strapped to his front, another to his back, seemingly unbothered by the load. He was tall and strong with generic good looks.

I took one look at him and I knew his story. I knew the second pack belonged to his girlfriend – a tanned beauty with long legs and perfect teeth. I knew they were in their thirties – smart, with high-paying jobs back home…

-

It’s funny how certain courses of action simply don’t occur to us, especially in the moment. Even in retrospect we don’t see all we could have said or done. We stay inside the square, behave in the expected ways, conform to expectations, follow written and unwritten rules.

What’s more, we do so even when we have good reason to do otherwise. Or at least, most of us do, most of the time.

I recently heard the journalist David Brooks interview historian Kate Bowler.

-

There are people in this world who spend their days watching people, making people up, and trying to read minds. They are intent on knowing who these people are, and how they think, and why. This fascinates them utterly.

The Pulitzer-prize-winning novelist Elizabeth Strout often talks about this fascination, which she’s had since she was young, in interviews. In a 2017 New Yorker article she recalls attending to a stranger so closely she almost felt ‘her molecules move into me—or my molecules…

-

Christmas is fast approaching, but you could be forgiven for wanting to slow down your purchases. With the rise of the mindful, minimal-waste consumer, many are looking for gift-giving options that don’t cost the earth. Enter, the pre-Christmas stuff swap.

-

Email templates save us time, but at what cost?

A newsletter that I subscribe to shared a link last week that made me cringe.

The newsletter, which is aimed at freelance writers, linked to a site with a range of templates to “help you say no in a variety of situations”.

If the link was to an article with advice on different ways to say no, complete with principles and the odd example, I don’t think I’d have flinched, but it was to templates — “and if you’re a Gmail user, you can import them all for use right into your email account”.

-

A few years ago, the editor behind one of Australia’s most lucrative non-fiction writing prizes changed its rules. The Saturday Paper’s Erik Jensen decided the Horne prize would no longer consider any essay purporting to ‘represent the experiences of those in any minority community of which the writer is not a member’.

-

Older people are often undervalued and overlooked in our society – to their detriment, and ours.

A stranger knocked on our door the other day. She was promoting a service for older people who live alone. To counter the risk of an accident or sudden illness going unnoticed, a person could sign up to have a Red Cross volunteer call them every day.

It was heart-warming and heart-breaking; wonderful that an organisation was intervening to address the frightening risk of solitary suffering… -

According to a friend of mine, when I talk about feeling embarrassed, ashamed or misunderstood, my hands become claws and I run them down my face with exaggerated angst. I hadn’t realised I did that but as soon as she said it I knew it was true.

While still performing that move, we identified another: reeling in rope, cast too far out, at frantic speed. Both feature often when I talk about my writing – about the risk of sharing words I might regret.

-

I’d been reading Richard Powers’s novel Bewilderment — the story of a nine-year-old boy grieving his mother, the story of an unmoored father, raising his son in a dying world — when I heard a philosopher on the radio offer an all-encompassing solution to human suffering.

In Bewilderment, the boy’s mother, a passionate animal rights activist, would say the Buddhist prayer, “May all sentient beings be free from needless suffering”, when she tucked him in at night…

-

She was about my mother’s age, petite with long grey hair and an equally delicate dog. I steered the pram to the edge of the footpath to let her pass. Instead of walking by, she stopped and spoke.

“I’ve been watching you for years!” she said.

What’s more, I wasn’t surprised.

Over the years I’d sometimes wondered whether anyone in our neighborhood had ever glanced out their window before dawn and squinted at a strange, shadowy figure walking down the street. I imagine the sight…

-

Photographs aside, the record of my children’s childhood I’ll treasure the most is one I never planned to keep.

It began when, at the age of two, our first child started speaking in sentences. I was so delighted by the gems he came out with—so eager to share them with my husband and yet so prone to forgetting them before he finished work—that I’d reach for my phone.

“The act of sharing those gems, of having friends and family delight in them too, added to the fun …

-

Michael Rosen reminds us all that sometimes, the smallest achievements are the most extraordinary

I happened upon a wonderful book this week: a first-person account of an old man’s rehabilitation following a serious illness. I found it at the library and, later in the day, read it to my kids.

The book, written by Michael Rosen and illustrated by Tony Ross, begins with a drawing of a greenish-blue face emerging from a white sheet and the words: “I was ill. I was so ill I couldn’t get up.”

(more…) -

One of the best opinion pieces I’ve read this year was a friend’s Facebook post. It was 1,600 words long. He wrote about moral choices that have no clean solutions; about how sometimes a path of action must be “walked with tears”.

Among the thoughtful, appreciative comments that followed, I noticed one that began, “Couldn’t read all of this”. She went on to say she’d be removing him from her Facebook as words couldn’t express how strongly she disagreed with him. I began to lament the author’s…

-

My kids brought their report cards home last month. I’d been thinking about the election campaign, and about society’s obsession with productivity. I’d been wondering how ‘the unemployed’ and ‘pensioners’ might feel — like a burden? Like a problem to be solved?

I’d been thinking about my own productivity too as an employee, as a freelancer, as a parent; about what left me feeling satisfied, worthy, competent, or guilty, unproductive, unfulfilled… -

The first question I ask ecologist and jewellery maker Dydee Mann is not the one I planned: “Do you want to tell me why you’ve brought dead birds to my house?”

The threatened species biologist is visiting me for an interview during her lunch break. She’s just come from the museum, where she borrowed a box of swift parrot specimens for a training course she’s running. She wants attendees to see the birds up close and appreciate their unique beauty.

-

In Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s 2019 novel Fleishman is in Trouble there is a scene where the main character, Toby Fleishman, is having dinner with a woman he found on a hookup app, but has only ever met for casual sex.

As she studies the menu, Fleishman studies her: “If you looked closely, she had about two centimetres of gray hair at her temples. She had said she was forty-five. She might actually be forty-eight. That’s almost fifty… She reached across the table to take his hand. He squeezed hers back. He never realized her arms were so hairy…

-

We met over a damsel in distress. The damsel had just given birth to twins and urgently needed a bar fridge to store breast milk in. I posted a request on our neighbourhood Facebook page. Within minutes, a lady named Veronika had replied offering a “lovely” fridge we could keep for several months — and call “Louise” if we wanted to. She was even willing to delay a non-urgent outing for potting mix and chook food, so I could pick the fridge up that morning.

-

We don’t need to cross the creek—we have no destination—but nobody points this out. By the time the rest of us have started rolling up our jeans, Anna’s are off and she’s thigh-deep in icy water. It’s the only way, we see this now, and so we do the same.

The reason we’re in the middle of nowhere, crossing a creek in our undies, is that we’ve run away for a girls’ weekend. We’ve rented a cottage surrounded by fields and sheep, water and sky; we’ve no one to care for, nowhere to be.

(more…) -

On the first day of our country holiday, I almost had to drag my eldest son to the willows. I’d been picturing the fun our boys would have there—climbing from one tangle of branches to the next, swinging and jumping and darting and dropping. As soon as the car was unloaded, I struck:

“Let’s go to the willows! The fields! The creek! Let’s explore!” He said I could take his brothers, he would stay behind. I said fun was compulsory…

-

The stars were so bright that instead of looking where I was walking, I kept looking at them. Then I stopped walking—maybe even breathing—and stared.

I’m no expert on the constellations, but I was sure that if the sky usually contained a line of about a dozen stars, I would have seen it before. And then I noticed the line was moving.

I blinked. I exclaimed…

-

A few years back, I set myself the challenge of interviewing twelve of my friends and combining their stories. I was astonished by how much I learnt in the space of one uninterrupted hour.

One friend talked about how trapped she felt during her (planned) pregnancy, another recounted a narrow escape from an abusive relationship, while a third talked about the moment he realised, for the first time, he didn’t actually have to do what adults told him.

-

If we go looking for problematic speech, we’ll probably find it

A friend of mine who works on a university campus spends the start of every year meeting students. This year she reported that — to her disappointment — no one asked her where she’s from.

She said this was a first. Did it mean that 15 years after immigrating, her accent had softened to the point no one noticed it? Or didn’t people care where she was from?

-

I’d been thinking about friendship and therapy, and friendship as therapy. I’d read Lori Gottlieb’s Maybe You Should Talk to Someone, and thought about how close a therapist and client might become. At the same time, I’d been thinking about my closest friends, and the therapeutic potential of friendship.

I’d thought about the rising demand for counselling—at last the stigma was lifting, as it should—but I’d wondered, too, if there was a corresponding decline in the depth of our friendships.

-

It happened at the theater. The kids and I had just seen a 90-minute Peter Rabbit production and my 10-year-old said he was going to the bathroom. I told him there’d be a huge queue. We were heading to the library next, which was practically next door, and so he could go there. In retrospect, I should have made sure that we were on the same page before I turned away.

-

My son had COVID-19 and we were under house arrest, so when a friend asked if I needed anything — a cake delivery, perhaps? — I made no attempt to dissuade her. She arrived at the door with a huge slab of mud cake layered with creamy chocolate ganache. I cut a sliver, just to taste, then another. I cut a generous slice for my husband, and generous slices for our kids. I cut a sliver, just to taste. And another. Technically I never had a slice.

-

Regardless of whether you’ve read Hanya Yanagihara’s 2015 novel A Little Life, chances are you’ve heard of it. It’s been promoted as “an immensely powerful and heartbreaking novel of brotherly love and the limits of human endurance”, and it’s become notorious for testing many a reader’s endurance.

Many, myself included, have described it as one of the most traumatic books they’ve ever read.

-

I’ve often wondered what it would be like to read a mind: to access a person’s unfiltered consciousness, to compare it to my own. I imagine the experience would be a bit like reading character-driven fiction, and a lot like reading Lucy Ellman’s Ducks, Newburyport.

Ducks, Newburyport is a novel based on a stream of consciousness that runs without ceasing for more than a thousand pages. The stream contains no pauses,

-

What you read and where you go can sometimes be the same thing.

I was scrolling through my camera roll, looking for some summer snaps to send to my grandparents, when I noticed an unexpected theme. Interspersed among photographs of action, lit by sun, were just as many flat, uncolored images—ink on paper, black on white: photographs of text.

It didn’t come as a surprise; I’ve had this habit for some time. I’ll read a line or paragraph I don’t want to forget—a passage that has moved me or intrigued me; a phrase that sounds especially beautiful or rings especially true—and make a copy I can keep. They’re fragments I might want to ponder further, to reference in my writing, to share with a book-loving friend.

(more…) -

My husband and I married young and on a budget. His late grandfather was known for saying people shouldn’t make any major life decisions before they turned 20; my husband was 19.

My engagement ring cost cents not dollars—it was a gummy ring I promptly ate. Our wedding bands were $50 each, and I bought a dress on sale for about $100. It wasn’t technically a wedding dress but it looked like one to me. We didn’t want to choose which friends and family to invite so, despite our budget, we made it open-invite.

(more…) -

I’ve always found it strange—and strangely wonderful—that one person can adore a certain type of food or music, leisure or work, that another will detest; that one person can find an artwork profoundly moving, while another doesn’t even consider it “art”.

At the same time, most people seem to agree that sunsets and stars, waterfalls and mountains, forests and flowers are beautiful; or at the very least, “not yuck”.